While researching The Global Playground, I couldn’t help to look into the emergence of playgrounds in our urban environment, in full knowledge that playground was just a metaphor in the project. Playgrounds have shaped our built environment in many ways over the past few decades, but they are oddly exclusive places for children and parents/carers, often in very public areas of the city.

Children played in streets and open fields before urban spaces became too dangerous as vehicles start to dominate. In Europe, early forms of a dedicated, public play area started life as sand pits in Berlin, inspired by Friedrich Froebel’s ideas on play. Early examples of play areas were strange sights in today’s world: boys and girls played separately, and organised play was supervised by instructors. Post WWII, children found play in the remnants of bomb sites which inspired the idea of adventure playgrounds. These exciting play areas are made of found and discarded objects and children are free to roam and explore like going on an adventure. However, there are many places in the world where the introduction of an enclosed, public playground is an imported idea. Without the development of adventure playground and organised play in the earlier part of the 20th century, children play in the open, wherever they are allowed. The idea of play shifted from these open spaces to an enclosure, from self-initiated exploration and group games to designed play. The play structures in a playground, to this date, are often made from metal and they all have slides, swings, roundabouts and seesaws. Adults somehow settled on what a playground should consist of, and it doesn’t really matter what climate you are in. I still remember the burning sensation while sliding down a very hot slide in the height of summer in Taipei when the temperature goes way beyond 30 degrees Celsius for months.

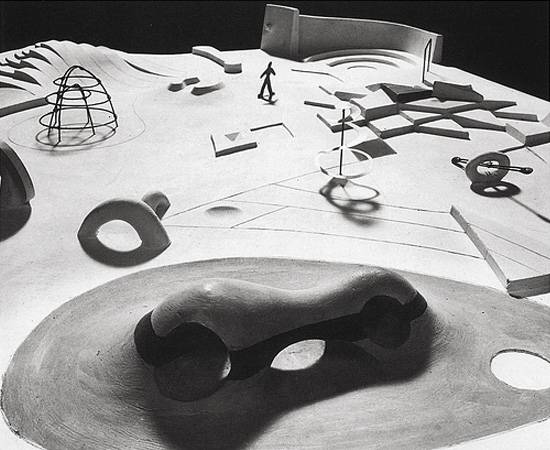

Exceptional urban playscapes designed by Isamu Noguchi, architect Aldo van Eyck and contemporary designers inspired by ‘natural play’ are few and far between. We have become accustomed to these universal, exclusive spaces, and parents rely on them for safe outdoor play in an otherwise dangerous city environment designed mainly for cars.

Playgrounds, therefore, compartmentalise our experience in public spaces. The demarcation of play runs deeper than physical boundaries. Playgrounds are mainly designed for children. What about parents? When my son started walking, I found myself in playgrounds minutes away from my home that I never visited before. There are as many carers as there are children, yet we stand around, assist, or observe our children and wait till boredom strikes, understandably, as the ones who are not playing.

Play is universal and is not tied to playgrounds, but modern playgrounds shed some light on how we adults perceive play. We want children to be physically active, sensorially stimulated, interact with others and be enthralled. But, children don’t need playgrounds to play. Early forms of swings in Greece and China don’t appear to be for children but for adults. Games and sports make rule-based play. Those who want to play find playgrounds everywhere. The players make the playgrounds.

Japanese American sculpture Isamu Noguchi’s visionary designs are great examples of inclusive play in the sense that everyone can play, young or old. There are structures to climb, which is an active device, and swings, a timeless invention for passive play, that is to allow the body to experience movement without moving. There are contoured surfaces for seating, integrated as part of the playscape rather than a park bench. It is sculptural in form and it is intended for the general public, the young as well as those young at heart. I wish these playgrounds will become the norm one day, perhaps alongside the movement of pedestrian-priority thinking in urban planning.